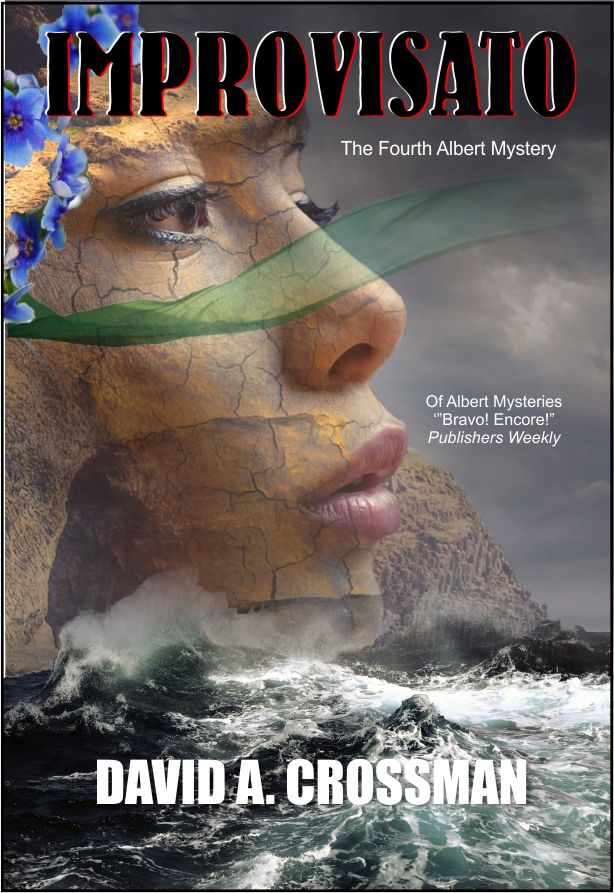

Improvisato

“Albert is one of my all-time favorite sleuths.” New York Times bestselling author Tess Gerritsen

“…shines with comic brilliance. Crossman has a gift for creating characters…who should show up in further adventures of Albert. And there should be more.” Chicago Sun-Times

“If you have ever aspired to be a private detective, here is some hilarious inspiration. Crossman’s delightfully offbeat tale of wacky academic politics contains a host of bizarre characters and an inexplicable homicide. Albert is indeed a unique, likeable operative. I certainly look forward to an encore.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch

In Brief:

The year is 1986. It’s been four years since Albert fell off the edge of the world; a world he wished would forget about him; forget he ever existed.

He hadn’t really existed though, had he? The School had sheltered him in an academic womb – its winner of a specially-created Nobel Prize, the Guggenheim Fellowship, seven Grammy Awards and two Pulitzers – hustled around the planet from concert stage to concert stage, seeing only fleeting glimpses of life from the back of stretch limousines and penthouse hotel rooms.

Then murder entered his life.

For six months after that, one hideous death led to another, like a string of blood-red pearls, trailing Albert to the edge of the abyss; forcing him out of the womb, naked and exposed. Finally, he’d fled to a place of safety, where even Death couldn’t find him.

But it did.

SAMPLE CHAPTERS

Improvisato

The fourth Albert mystery

by David A. Crossman

Chapter OneFebruary, 1987

ooooAlbert was struggling to make his face look like his ears were listening to whatever the too-much-woman in too-little-dress was saying but, try as he might, he couldn’t detach his retinas from the cat on the windowsill that was retching up its insides. The exercise didn’t seem to be causing it undue alarm which, to Albert, was alarming. He didn’t imagine that, were he in similar circumstances, he’d take it so calmly. The curtains would probably be in shreds.

ooooNobody seemed concerned; that was another strange thing. Some of them, at least, saw what was happening, even nodded their wine glasses in the direction of the afflicted quadruped and smiled or chuckled. Where were the animal rights people? Albert had just managed to stuff his natural reticence into a small, neat box labeled ‘Do Not Open’, and form a one man Feline Aid Society (FAS), when something amazing happened: the cat’s insides were no longer . . . inside . . . but sat in a moist, deflated ball upon the windowsill.

ooooThe cat, licking its lips, cocked its head at the steaming, yarn-like mass, then, as if aware that he was being watched, looked at Albert as if to say, ‘Well, would you look at that?’ then started to lick itself.

oooo“Hairball,” said a man.

oooo“Albert,” said Albert. He was always quick to give grace when names were forgotten or confused. He did it all the time.

oooo“Beg your pardon?”

oooo“I’m Albert.”

ooooA crinkly kind of expression scrunched across the man’s face. oooo“Yes, Albert” he said, slowly. “I know. I’m Walter. Your press agent? Remember? Three years now.” The light of recognition was not forthcoming. “Walter?”

ooooAlbert considered him much the same way the cat had considered the hairball.

oooo“Franklin?”

ooooNow things were getting confused. Walter or Franklin? Albert looked quickly around to see if someone else had joined the conversation. “No, Albert. It’s me. Walter Franklin, remember?” He took Albert paternally by the elbow and extracted him from the cloud of perfume surrounding the woman and whatever she was saying, and guided him toward the cat that now sat contentedly in the window as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened. But there were its insides, outside.

oooo“Weirdest thing in the world, to me, when a cat coughs up a hairball like that,” said Franklin. “But look at him, already working away on another one.”

ooooIf a press agent could know so much about cats, why didn’t Albert know about anything but music? Of course, he’d learned a lot in the last few years—most of which he wished he hadn’t—but some people knew about things like cats and some people didn’t. He fell in the latter category. He knew geography, though. And accents. Maybe that’s the way it was with everyone. Maybe everybody knew a couple of things well and the rest of the world, outside those few things, was just as fuzzy to them as it was to him. Albert was excited by the thought. Maybe the only reason it seemed everyone but him knew everything was that, when they were all around him, each talking about the one or two things they knew, and those one or two things were different for each person, it just seemed as though they all knew everything. On one of the walls in the vestry of the church where he’d gone to Sunday school as a very young child—before anyone knew what he was—there had been a painting of a man named Paul having an epiphany, which apparently had something to do with falling off a horse and holding up his arm to shield his eyes from a blinding light. He must have felt much the same way Albert was feeling now. What if, after all, he wasn’t the misplaced freak he’d come to think himself to be? What if he was just another in a vast population of freaks? Wouldn’t that make him perfectly normal?

oooo“Your sister wants to see you,” said the press agent, whose name Albert had already forgotten, but he was torn. On the one hand, there was the press agent, on the other, Abigail Grace. His sister used to play the saxophone. Not very well but, of course; she was female. She had always been older than he. Not chronologically, but in every other way. She was, to Albert, the embodiment of efficiency. Not only did she seem to know everything that eluded him, she had always reminded him of the fact, which compounded the impression. Jeremy Ash knew everything, too, even though he had no legs. No, don’t go there. That would just bring up a lot of other thoughts that wouldn’t be about what he was thinking about. Which was? Oh, yes. Abigail Grace. Their mother had always told him that, when in doubt, “Do what Abigail Grace says.” That stopped, for the most part, when The School took charge of Albert and Abigail Grace moved to Florida when Mother moved there from Maine upon reaching the age when the move was, apparently, mandated.

ooooHe wondered if he still had to comply with the command now that she was dead. Mother, not Abigail Grace. In the parlor. In a casket with the top opened. That struck Albert as odd. Why did people want the top open on a casket? Dead people weren’t very pleasant to look at, after all. At least, he didn’t think so. And he’d seen a lot of them lately. Too many.

ooooWhy, then? Was it to assure the living that the deceased wasn’t just pretending to be? Or maybe it was to give the dead person one last chance to sit up and shout: “Let me out of here!” in case they weren’t. Dead. Abigail Grace was in the kitchen, which was at the opposite end of the hall where Albert and his press agent— Smiley? Heathcliff?—stood.

ooooAlbert, taking his leave, decided to take the long way, through the parlor. At his approach, the little knot of black-clad people, presided over by his Uncle Albert that had been milling about the coffin—drinking wine and reassuring themselves that the deceased really was—departed, forming a sort of human funnel that drew him toward the casket. He looked down at his mother’s face. Her mouth wasn’t moving. That was a phenomenon. Even so, he could hear what she was saying; what she always said: “I’m doing this for your own good, Albert. If you only knew.” This usually meant that something unpleasant was about to happen.

ooooThe first time he recalled hearing those words, they had been the last thing she said as she closed the door to the waiting room and left him alone with the dentist. Albert had read a book, or seen a movie, or was once told, or maybe had a dream about someone who worked for Hitler and enjoyed doing terrible things to human beings. The analogy made his teeth hurt. He wondered if those poor people had been abandoned by their mothers, trying desperately to derive

some slim comfort from the echo of those words: “I’m doing this for your own good, (insert name here).” ooooSomeone put their hand on his shoulder and patted it. “We’re so sorry, Maestro,” said the patter. “Emily was a wonderful woman. She will be greatly missed. So sorry.” Albert looked up to see a man with misty eyes and instantly three questions sprang to mind. First of all, as the man was apparently alone, who was the “we” in “we”? Secondly, what was he—or were they—sorry for? Had he/they somehow brought about Emily’s death? Third, who was Emily? He’d seen the name somewhere recently. Oh, yes. On the little bronze plaque on his mother’s coffin. Albert knew, from painful experience, that it happened all the time; person A would bring about the death of person B. Sometimes intentionally. Sometimes by accident. Sometimes not intentionally, but not necessarily by accident. All of which were, he suspected, irrelevant to the person whose death had been brought about. ooooHe’d heard that Indians used every part of an animal they’d killed and then did a dance, or sang a chant or something, as if that would somehow make the animal feel better that it had been killed for its parts. He stared at his mother’s face as people murmured around him. But it wasn’t her face that formed, at first, in the fluid of his sight: it was that of Tewksbury, who had died in a fire; it was Judge Antrim, who had been stabbed in the chest; it was Esperanza, who had jumped from a castle tower and become a ghost who slept with him sometimes; it was Harvest Lossberg, painter of cows, killed by a hatpin thrust through his neck; it was Welf the Potter’s son who had been buried alive, surrounded by a king’s ransom in treasure.

ooooMost of all, though, it was Melissa Bjork, who had died in his arms, with his name on her lips, and his heart in—wherever people put other people’s hearts. The coffin was a horizontal doorway to the grave, and they were all in there. Then it was his mother again. He felt like he should feel something. Everyone seemed to be expecting him to make a speech, or burst out crying, or fall to his knees, shake his fists and say, “Why! Why, Lord!” He’d seen that on the television news once; a little group of foreign-looking women were doing all these things at once because someone had set off a bomb that blew up their children. He had thought of putting the images to music at the time, but couldn’t think of anything sad enough.

ooooThat was years ago. He’d lived a lot since then. He’d loved. He’d lost. Now he could write a requiem in his sleep. He often did. He stared into the casket and whispered: “What am I supposed to do, Mother; Emily?” She didn’t answer. That, at least, hadn’t changed.

ooooThe cavalry arrived, in the form of Jeremy Ash, who rolled through the crowd—not being overly careful about running his wheelchair over people’s feet, which made progress easier. “You okay?”

ooooAlbert nodded mechanically. “Abigail Grace wants to talk to me.”

oooo“Do you want to talk to her?”

oooo“No. I want to go.”

oooo“Grab hold and wheel me to the front door.”

ooooAlbert did as he was told and, contrary to his expectations, no one tried to stop them. Within seconds he was at the front door. Another second or two, on the front porch. “Where to now?” Jeremy asked, though why he should, Albert couldn’t fathom. After all, it was he, Jeremy, who had contrived so smoothly to extricate them from what, to Albert, had seemed an inescapable situation.

oooo“Where do you want to go?” he asked.

ooooJeremy Ash answered as if he’d be contemplating that very question. “New Zealand.”

ooooAlbert knew where New Zealand was. He knew they spoke a form of English. He knew Angela McLauren’s older sister, Hester, lived there, in Christchurch, with her husband, what’s-his-name, who worked for the government. “Can Angela come?”

oooo“Sure, if she wants” said Jeremy. “She can grab the passports and meet us at the airport.”

oooo“Okay.”

ooooJeremy gestured for their driver who, in short order, settled the legless boy beside Albert in the back seat of the limousine and drove them to Logan—the nearest airport with connecting flights to New Zealand. “Call Mrs. Bridges and have her make the arrangements.” The driver got on the car radio, called the formidable woman with the day-dated bras who had become Albert’s financial manager, and relayed the instructions.

ooooAt the back of his mind, Albert wondered why the people who put other people in charge of things didn’t put Jeremy Ash and Mrs. Bridges in charge of everything. Just . . . everything. Albert watched the familiar countryside—dressed in snow, ice, and slush—slip by as they drove southeast toward I-95, every turn of the wheel putting that much distance between him and the scenes of his childhood: the farm where his sister, by now, was stomping and fuming without actually stomping and fuming—it was a trick she did with her jaw and her eyes—and his press agent was doing whatever press agents do when the one they’re agenting isn’t near enough to press. The place where Melissa Bjork and his heart were buried. Albert took no notice of the VIP treatment he received at the airport. People did whatever needed to be done to make sure what he wanted to happen—or, more specifically, Jeremy Ash wanted to happen—happened. That’s just the way it was. The way it had always been. Nothing special. Nothing different.

ooooSo it came as no surprise when he found himself—and Jeremy, and Angela—sitting in first-class seats on a flight to New Zealand, via Los Angeles and Tahiti, that just happened to be leaving within an hour of their arrival at the airport. Had he thought about it, which he didn’t, he would have assumed that Jeremy Ash had arranged it that way, and he wouldn’t have been surprised. For her part, Angela had found it surprisingly easy to adjust to a life in which she could have anything she wanted, whenever she wanted it. The other thing that had surprised her was that, now that she could have whatever she wanted, whenever she wanted it, she didn’t really want much. Perhaps it was that she didn’t want to take advantage of Albert—even though he had more money than Midas.

oooo Perhaps it was that, since coming to live with him and Jeremy Ash, and Mrs. Gibson—a formidable lady from a different planet than Angela had ever occupied, even in Tryon, North Carolina—she had come to appreciate other things.That, and prison, of course. That changes people, one way or the other. She knew, in accepting Jeremy’s invitation to come live with them, that she was surrendering herself—for the time being—to life in Albert’s slipstream. He occupied a rarified atmosphere, one in which the world accommodated itself to his needs, often before they were spoken. She had become one of those little fish that attach itself to a bigger fish and feast from the leftovers. ooooIt was better than starving, which she had done. It was better than stealing, which she had done. It was better than prison, where she had spent three years. It was better than busking in subway stations, running from the consequences of one bad decision after another. A lot better. The notion that had—early in their renewed relationship—percolated to the surface from the depths of her subconscious and formed a kind of determination was that she wanted to be a useful appendage for Albert, not a tumor that sucked the life from him.

ooooJeremy had been dubious. It hadn’t been his idea that she come live with them, even though he had been the one to extend the invitation. He had read Albert’s mind, even though Albert hadn’t known he’d been thinking it, and simply made it so. That’s what he did. The last few months, though, had convinced him that Angela was good for Albert. She did things for him that would never have occurred to Jeremy, because she was female. Of course, Mrs. Gibson was female, too, but she was more female in the “do as your grandmother tells you,” mold—not unlike the mother who, by this time, had probably been lowered into a six-foot hole in Maine.

ooooAngela, who seemed to be sleeping as Jeremy studied her from across the aisle, despite her sketchy background, had social skills that he lacked. She knew how to negotiate the minefield of upper-class mores and manners—where so much of what was said was unspoken—while he tended to plow through them in his wheelchair, leaving a lot of bruised feet in his wake. She knew how to dress Albert so he didn’t look like he’d walked through a laundromat, grabbed anything that came within reach and put it on wet. She could twist an uppity maître d’ in knots and spit him out in a wad. The same with bureaucrats and the denizens of officialdom. Jeremy had come to see what he hadn’t suspected of himself, that he, too, manipulated people through their sympathy for him. That’s okay. You work with what you’ve got—or don’t have—to get what you need.

ooooAngela had two other potent weapons he didn’t have. First, she was more than ordinarily pretty, and somehow unconscious of it, which made her disarming in a way that could be lethal. Novacaine and hot butter came to mind, for some reason. The second weapon was, from a psychological perspective, strange. While herself the child of middle-class parents of solid “know-your-place” British stock, she had at one time—and for a long time—impersonated her highborn classmate, Heather Antrim. And done so to such a degree of perfection, that she convinced herself—and everyone else— that she was Heather. How weird can you get? Angela wasn’t asleep. She could feel the eyes of Jeremy Ash upon her, though with what intent or to what purpose she couldn’t fathom.

ooooThe boy—not so much a boy anymore—was an enigma to her. While she was not unused to being stared at sexually and, though she sometimes sensed him looking at her that way, he most often seemed to go out of his way to seem to be ignoring her. But she knew he wasn’t. And that made her uncomfortable, and she reacted to that discomfit by being more abrupt with him than she meant to be. More sarcastic. Despite the fact that, not so deep down, she had tremendous admiration for him, and a kinship in their mutual love for Albert. Therapy had helped her understand that the border between truth and illusion, fact and delusion, was marked by the mental equivalent of Hadrian’s wall—pocked with holes in some places, missing entirely in others—and that she had wandered that strange country for a long time. Sometimes she wondered if she had altogether found her way out of it. How much of a fellow-traveler in those precincts was Jeremy Ash? Kept locked in a wedge of closet under the stairs in the home of his drug-addled mother for the first seven years of his life—all but naked, fed indifferently, never loved, never held, never cared for, never even standing to his full height until he was finally released from that little dungeon, upon which it was discovered his legs were too diseased to support him and had, in stages, to be removed—mightn’t he be even more an inhabitant of that horrible landscape than she?

ooooThe possibility that, of the three of them, Albert might be the most sane, was sobering. It also made her chuckle to herself.

ooooJeremy, seeing this, withdrew his gaze. What was she thinking? ooooAlbert was looking at the coffee in his cup. Something in the mechanism of the aircraft was making the coffee vibrate, creating an irregular pattern of concentric rings. Three rings equally spaced, then a fourth a little out of sequence, then a rest, repeat. 1-2-3-and-4-and-a-repeat An eighth note triplet, followed by a sixteenth rest, an eighth note, a dotted eighth rest, repeat. As the pattern established itself in his brain, it was joined by a melody. Then harmonies of 3rds and 5ths. No. Not 5ths, 4ths. As he listened, an underlying current of Gregorian plainsong bubbled toward the surface every now and then, subsiding almost to silence in between the pulses. Plainsong was voices. Music rarely came to him in voices. He tried to listen to what they were saying, but the words were Latin. He didn’t speak Latin. His mother had spoken Latin. She had attended the Latin School in Boston, so that was to be expected. She wasn’t speaking anything now. He mentally closed the casket on the last image he’d had of her to the accompaniment of the odd little requiem that the coffee had written. Would she approve of the piece? He didn’t know. Come to think of it, he didn’t know what kind of music she liked. She never listened to the radio or records. Come to think of it, she had never, as far as he could remember, attended his concerts. Come to think of it, he hadn’t known her; not at all. She must have been young once.

ooooHe pictured Abigail Grace, a young version of her old mother. But is that what Mother had been? A young version of her older self? Or had she been different, changed by her experience of life into what she became—upright, strict, proper, demanding, unbending, hard, but somehow sad? She must have been in love once. She got married, after all. Had three children. The one before Albert had died. She never talked about it—Albert didn’t even know if it had been a brother or a sister. Nor had she ever spoken of her husband, their father. There were no pictures of him in the house. Of course, there were no pictures of Albert or Abigail Grace as children, either, not until that one taken of the little family after his first concert at Carnegie Hall—she had attended that—Albert in the middle, with his hands at his side, Mother on his right, with her hands crossed in front of her, a mirror image of Abigail Grace, on his left. None of their bodies touching. None of them smiling. Albert looked out the window.

ooooHe’d never thought about his father, or, until now, that he no longer had no mother. Was he an orphan? Cities and towns, marked by sprinklings of lights, passed slowly below. Was he down there somewhere, as unaware of Albert as Albert was of him? The speckling of lights became blurry. He wiped at his eyes and, feeling something moist on his fingers, looked at them. Tears. “I love you, Mother,” he whispered. He didn’t feel it, but he wanted to, and he thought saying it out loud might help. Maybe if he said it often enough . . .

ooooThere was a light touch on his shoulder. “May I take this?” said the stewardess, taking the saucer between her thumb and fingers. He nodded. She took it. “Is there anything else I can get you?”

oooo“No.”

ooooShe hesitated. “I just wanted to . . . I’ve never done this before, and they’d skin me alive if they knew, but . . . would you mind?” She smoothed a napkin on his tray and handed him a pen. He picked it up, scrawled his name on the napkin and handed it back to her. oooo“Thank you. Thank you so much, Mr. . . .”

oooo“That’s okay,” Albert said. “You know, I think I’d like you to leave the coffee.”

oooo“But, it’s cold,” said the stewardess. “Why don’t I get you some that’s hot?”

oooo“No. I just want to watch it.”

ooooThe stewardess didn’t seem to know whether to take him seriously. “I, you mean . . . “

oooo“Just leave it,” said Jeremy Ash from the seat behind Albert. The stewardess sputtered a little protest, but did as she was told and went away.

oooo“Why New Zealand?” said Angela, when she and Jeremy caught one another’s eyes.

ooooJeremy shrugged. “I remember you mentioned it, when we were in London. Place I’d never thought of before, and it just came to mind when he asked where I wanted to go. Crazy, huh?”

ooooAngela nodded. “My sister’s there, somewhere.”

oooo“So you said. Haven’t seen her in a while?”

oooo“Not for dog’s years. I was just a kid. Wouldn’t even recognize her now, I shouldn’t think.”

oooo“We should look her up.”

oooo“I wouldn’t know how.”

oooo“You know her married name?”

ooooAngela nodded. “McEvers.”

oooo“First name?”

oooo“Hester.”

oooo“Hester McEvers. All we need’s a phone book.” Jeremy drew an inference from the silence that followed. “You don’t want to see her?”

ooooIt was Angela’s turn to shrug. She did. “I’m not sure she’d want to see me.”

oooo“She is real, though?” said Jeremy. “You haven’t made her up, the way you made up . . . .”

oooo“No! She’s real. She and her husband, Gilly. Gilbert. They’re real, and they’re really my sister and brother-in-law. More like parents, really. They all but raised me.” She became thoughtful for a moment or two, and Jeremy Ash let her. “If we find her, it will all come out, Heather, the accident, the impersonation. Prison. Everything.” Jeremy didn’t respond. The fact was self-evident. “It’ll be like living through it all again.” She looked out the window. “I don’t know if I want to put myself through it.”

oooo“Sometimes what we want to do don’t enter into what we need to do.”

ooooShe turned toward him and, in response to the smile that crept to his eyes, laughed and tossed a balled up napkin at him. “I hate you.”

ooooTo Albert, the exchange between Jeremy Ash and Angela—though he couldn’t hear all their words—was like music. A lullaby. Comfortable. Something he could curl up and go to sleep in. And he did.

Chapter Two

ooooAlbert’s first impression of New Zealand, as they stepped from the metallic cocoon into the bright glare of the latemorning sun, was that it was hot. “It’s hot,” he said. “It’s beautiful!” said Angela. “I love it already. Well done, J.” She patted Jeremy Ash on the shoulder as an assortment of attendants jostled one another to be helpful, carrying him down the ramp to his waiting wheelchair. Albert hadn’t really been listening—as was his custom—when the stewardess told the new arrivals that a warm Maori welcome awaited in the terminal and, therefore, was unprepared for the assault by a horde of pudgy, spear-wielding, heavily-tattooed and very unhappylooking dark-skinned men in grass skirts.

oooo“Isn’t this amazing!” said Angela as two of the attackers, eyes-bulging like ping-pong balls, advanced within poking distance and, punctuating ominous grunts with stamps of their feet, wagged prodigious tongues at her as if intent on strangling her with them. “What a welcome!”

ooooAlbert required a restroom, and a change of clothes.

ooooSome thirty minutes later—his material needs met—he settled back into the limousine. It had been a very long flight, and he was tired. He lit a cigarette, and a thought occurred to him. “Where are we going?”

oooo“It’s a little place called the Braemar Hotel. Downtown,” Angela replied. Proud of the arrangements she had made on short notice, she was eager to tell him all about it—how she had made good use of her time while he and Jeremy Ash were in the men’s room to ask the airport concierge where they could find the most comfortable, quaint place in town, and how he had suggested the Braemar without hesitation. After five minutes further discussion, she felt she knew the place. Within ten minutes its three guest rooms had been reserved exclusively and indefinitely for Albert, Jeremy Ash, and herself. And the concierge had enriched his personal coffers with both a ten percent commission and a gratuity gratefully received from the generous American.

ooooThe rooms at the Braemar were, of course, occupied, or were already booked by others but, once the innkeeper discovered who he was to be hosting, and Angela had offered each guest, or would-be guest, a fistful of dollars and first-class accommodation at the hotel of their choice for their inconvenience, objections were quickly and quietly overcome.

ooooAlbert didn’t know any of this, and it didn’t occur to him to ask.

oooo“I hope you like it.”

oooo“It will be fine,” said Albert. It was easy to please someone who didn’t really care.

ooooJeremy Ash read Angela’s disappointment. “Tell me about it.” By the time they arrived at the hotel—more a guest house, really—a half-hour later, Jeremy felt he could negotiate the place blindfolded. Only one consideration seemed to have been overlooked. “No elevator, huh?”

ooooAngela hadn’t thought of that. “No. I . . . I didn’t think . . . I was so excited. I forgot.” Jeremy could almost hear the air squeak out of her little pillow of custodial pride. She seemed to deflate before his eyes. “You do these things much better than I.” oooo“Don’t worry about it. If those guys in the hula hula skirts at the airport are anything to go by, it won’t be too hard to find one or two of ’em to toss me around.” And that is how, by day’s end, Albert’s entourage was—pound-for-pound—tripled by the addition of Wendell, a native in the mold of those who had assaulted them at the airport, only—in the refined spaces of the Braemar—much larger.

ooooHe had been highly recommended by Mr. Sweetman, the proprietor, who called him a ‘man of all work.’

oooo“A wonder with the heavy liftin’ is Wendell,” said Mr. Sweetman, with a nod toward the monolith in question; a cross, it seemed to Albert, between Buddha and Stonehenge, who could crush Jeremy Ash with an eyelid. Concerns along those lines were soon dispelled, however. Wendell handled Jeremy Ash like a hothouse flower, and called him ‘Little Pakeha.’ Albert had heard somewhere a story of a gentle giant. Goliath? No. He hadn’t been gentle. Big Ben? Anyway, but for the name, it might have been a story about Wendell.

ooooJeremy Ash, for reasons of his own, called the giant, Otis, and that made the giant laugh in the depths of his eyes and the dimples on his cheeks. Everyone was happy. Albert was happy. Mr. Sweetman had a tendency, when he spoke, of leaning toward his principle hearer. He leaned at Albert over his soup at dinner that evening. “I’m afraid we don’t have a piano,” he said. oooo“‘Perfect love casts out fear,’” said Albert.

ooooSweetman seemed to be considering this. “Yes. To be sure.”

ooooAlbert wasn’t really worried. There were at least four pianos in New Zealand; he’d played them on previous concert tours of the country: in Christchurch, Dunedin, Wellington, and Auckland. South to north. Somebody had probably planned it that way.

oooo“There’s one at the Rivens’, two doors down.” said Mr. Sweetman, whose Adam’s apple bobbed as he spoke, making his yellow-and-black polka-dot bowtie rock slightly back and forth in a mesmerizing way. He turned and leaned toward Angela. “Retired Colonel MacAulay Rivens,” he said. “Mac, we call him.” He leaned back at Albert. “Just Mac.”

oooo“Does he play piano?” said Albert. Not that he cared. He just wanted to watch Sweetman’s necktie twitch.

oooo“I shouldn’t think so,” said Sweetman, sitting suddenly back as if surprised by the suggestion. Then he leaned forward again. “His wife died not three months since.”

ooooAlbert’s eyebrows interrogated one another. Was it not possible to play piano if your wife was dead? This was a new and troubling thought. It hadn’t applied to Melissa Bjork. She had died in his arms, but the fact hadn’t affected his playing, though his music had changed. Of course, they hadn’t been married, just . . . well, not married.

oooo“I don’t think we’d wish to intrude on his grief,” said Angela. ooooThat’s why Albert liked having Angela around; she knew what to say, and when to say it, and how to say it in a way that made the person she was saying it to feel as if, at that moment, they were the only one in the world. That she cared.

oooo“Sometimes that’s all people want,” Albert thought aloud. He hadn’t meant to. All eyes turned toward him, except those of Wendell—who occupied the end of the table opposite Mr. Sweetman—and were intent upon his dinner which, with a broad grin at Sweetman he had earlier commended.

oooo“Mmm. Puha and pakeha!”

oooo“Pardon?” said Mr. Sweetman.

oooo“Nothing,” said Albert, bending his head toward his soup, and silencing his tongue with a spoonful.

ooooInstead of what he was thinking, their host said, “Unfortunately, grief’s not an exclusive commodity on Parliament Row these days.”

oooo“I’m sorry to hear that,” said Angela. “Troubles?”

ooooSweetman inclined toward his lovely young guest. His spoon, from which his inverted reflection regarded him with interest, awaited his pleasure halfway between his mouth and his bowl. With his other hand he held up three fingers. “Suicide,” he whispered, bending one of the fingers. “Accident.” He bent the second finger. “And Mrs. Rivens . . . two doors that way.”

oooo“How horrible!”

oooo“What happened to her?” said Jeremy, who had been uncharacteristically quiet until now, no doubt contemplating the great mysteries of life, thought Albert. That would explain why he always had an answer when one of them sprang up.

oooo“Murdered.”

ooooThe voice that spoke the dreaded word that had pursued Albert, Angela, and Jeremy Ash for the last four years, was not that of Mr. Sweetman. It was, therefore, toward Wendell that all heads but Albert’s swiveled.

oooo“Now, now Wendell,” said Sweetman, tapping the edge of his soup bowl with his spoon as if calling to order the meeting of some secret fraternal order. “Let’s not trouble our guests with all that business . . . especially at the dinner table.”

ooooWendell shrugged, which, on an island notorious for geological instability, was probably ill-advised. “It’s just so.”

ooooMr. Sweetman, thrusting his neck out to its fullest extent—not unlike the giant turtles on the Galapagos—pivoted his head in a sweeping motion from guest to guest, none of whom could claim to be the exclusive recipient of his remarks. “That’s pure conjecture,” he said earnestly. “Not a shred of evidence to support any such thing. Not a shred. Just ignore him.” He waggled his spoon—which was proving to be a very versatile instrument, prompting Albert to wonder why conductors didn’t use them to direct orchestras—in the direction of the edifice opposite him. “Poor Colonel Rivens. You should be ashamed, Wendell. As if the man hadn’t enough to contend with—his wife dying like that—and to be accused by innuendo! Deplorable!” He waggled emphatically. “I’ll not have it.” Pause. “Do you hear?” Both dimples receded from the cheeks of the wagglee, who lowered his head perceptibly, but did not stop eating.

ooooAngela and Jeremy exchanged meaningful looks, interspersed with sidelong glances at Albert, gauging the effect upon him of the direction the conversation had taken. ooooAlbert, who had come to suspect, in light of recent history, that people were murdering each other all around him—and probably had been all his life; he’d just been too thick to notice—simply sighed into his soup. “Even here,” he said. Who knew how long he’d been stepping over corpses, unaware?

oooo“Well, that’s tragic,” said Angela. “But it’s nothing to do with us, Albert, so let’s not let it spoil our little holiday.”

oooo“No!” Mr. Sweetman agreed. “By all means not! Nothing whatever to do with you.” He sat back in his chair as the maid took away his soup bowl and replaced it with a steaming plate of fish, rice, and vegetables. “Have any of you been to New Zealand before?”

oooo“Just rooms,” said Albert. He was staring at his soup, as if expecting it to do something interesting. “Concert halls and hotel rooms.” As these venues were, apart from their acoustics, the same everywhere. He’d never really been to any of the countries he’d visited. In fact, his recent excursion to Britain aside, he hadn’t really visited any countries at all; just their concert halls, airports, reception halls, and hotels: concrete cocoons with carpet. “Just rooms.”

oooo“Well!” said their host, with as much enthusiasm as one can inject into a single syllable. “We’ll have to remedy that, won’t we, Wendell?”

ooooWendell nodded, but didn’t reply. He, too, seemed to be expecting something of interest to take shape in his soup bowl—an empty bowl, in his case.

ooooFor the next half-hour or so, Mr. Sweetman—New Zealand born and bred—held forth on the glories, curiosities, enigmas, legends, geology, geography, flora, fauna, and history of the Island of the Long Cloud. “I reckon God’s a sculptor,” he concluded, “And this is His masterpiece. The rest of the world is just the bits he threw away. And you’ll not convince me otherwise.”

oooo“Where else have you been?” Jeremy asked.

oooo“Where else have I been!?” said the landlord. “Why would I go anywhere else?” He slapped the table. “I reckon if you’re in Paradise, you stay put, like Adam should’ve done.” And that concluded the discussion to his satisfaction. Nonetheless, he added, “One doesn’t journey, when he’s been born at the destination.”

ooooNot, however, to Jeremy’s. “There are lots of beautiful places in the world.”

oooo“Oh, no doubt, no doubt!” said Sweetman. He sat back, squinted at the ceiling as if he saw something there besides the ceiling, and patted his belly. “Not sayin’ there aren’t. Not at all. But there’s beautiful, and then there’s beautiful.”

ooooJeremy Ash inhaled to put wind behind an assault on Sweetman’s logic, but Angela stuck a pin in him. “Well, I suppose we shall have to see for ourselves . . .”

oooo“And so you shall, won’t they Wendell?” He didn’t wait for Wendell to reply, which was just as well, since Wendell hadn’t been listening. “Tomorrow, if you like, he’ll drive you up to Parua Bay. Good a place as any to start. Righto, Wen?”

oooo“Parua’s good. I’ve got cousins there.”

oooo“He’s got cousins back of every bush in the country, does Wendell. Good on ya, then. Tomorrow morning after breakfast. Get ready to fall in love.”

ooooAnd so it was that, sometime shortly after noon the next day, Albert and company found themselves sitting under a tree overlooking a beach of copper-colored sand. ooooAlbert had never, as far as he remembered, sat under a tree, with or without an attractive girl, a legless boy, and a large Maori. Nor, to the best of his knowledge, had he ever seen or sat on a beach. He’d seen pictures, of course, but the sand in pictures doesn’t get in your shorts, which is what Albert was wearing. Another first. Nor was the ocean in pictures wet, which, judging by Angela’s outfit—what there was of it—it was. She had, almost immediately upon arrival at the beach, plunged into the ocean for a swim. When she emerged, a quarter-hour later, she brought a good half-cup of it with her, mostly in her hair, which she proceeded to distribute by shaking her head. ooooAngela had a lot of skin, and it went in and out and up and down in ways that invited observation. It was also, Albert saw as she sat beside him, very white, but not as white as his own. He wondered if his legs had ever been out in the sun. He’d never really thought about them before. He did so now. They were covered with curly black hairs, sprinkled here and there with gray ones. His skin was not just white; it was almost translucent, revealing a network of blue veins. ooooThey were skinny and boney and, taken altogether, didn’t have a lot in common with Angela’s.

ooooShe was twiddling her toes in the sand and making contented moaning sounds, deep in her throat. “Take your shoes and socks off, Albert,” she said.

ooooIt was his custom, except on rare occasions, to do as he was told. He did so now, revealing feet that were, if anything, whiter than his legs. He tucked his black socks into his black shoes and set them carefully aside. Angela rubbed her toes against his.

oooo“There. That’s better, isn’t it?”

ooooAlbert had never had a damp, nearly naked girl rub his toes with . . . anything. So electrifying was the jolt that surged through him, that he wondered where she was plugged in. Almost instantly he withdrew his feet. Almost instantly. But the residue of that touch was slow in abating and only with the passing of time did the hairs on his head begin to settle back into place. It was one of those times he felt it would be good to think about something else and, as if on cue, the breeze brought him a sudden peal of laughter. He looked up to see Jeremy Ash in his wheelchair in the surf.

ooooBeside him, Wendell sat in the gentle waves that ebbed and flowed around him the way they did around any other natural feature. Both of them were facing the ocean and contemplating something amusing in the vicinity of Wendell’s feet. The ocean was a noisy thing. Albert closed his eyes and distilled the sounds: the “hush now” of the wavelets breaking on the beach, and the long, low exhale of the sands as they chased them back to the sea’s embrace. In the interval, a muted chorus of silvery giggles as the water gathered for another assault. The rhythm was lazy and slow, like Summertime, and the livin’ is easy. So this is what that meant. Beyond and beneath it all, the soft, ominous thunder of waves, breaking on the ledges outside the half-moon cove where they sat; the exultant splash of waves momentarily escaping the maternal clutches of the sea, before collapsing in sibilant surrender. Jeremy was first to see the body.

Chapter Three

ooooEven as he followed Angela’s footprints across the sand, Albert felt part of himself beginning to slip away, removing itself to the relative safety of his psychological storm cellar. What remained of him walked mechanically toward the body with which the tide was playing give-andtake with the shore, about twenty feet from where Jeremy had been when his cry rang out; where Wendell still stood, distraught but unmoving, repeating, almost chanting, a single word: “Tabu! Tabu!” The effort it had taken Jeremy to propel his wheelchair through the sand to the dead girl—for a girl, Albert could now see, it was—had exhausted him. He sat over the body, panting. oooo“Isn’t there anything you can do?” The question was directed at Angela who knelt in his shadow, surveying the victim who had been lying face down. She turned her over just as Albert arrived to play his part as a helpless bystander. He was cogent enough, at least, to recognize that the girl was oriental, and to be amazed at how Angela’s hands played swiftly upon various points of the body—the wrists, the neck, the eyes—as if it was a musical instrument. No music was forthcoming.

oooo“She’s still warm,” said Angela. “Go call the police!” She fell upon the body like a fury, pumping the girl’s chest with the heels of her hands, then pinching her nose, sealing her mouth with her own and blowing into the corpse as if it was a balloon. She did this several times, working herself into a prodigious sweat, before realizing that the shadows around her hadn’t moved. “Albert! Go call the police!”

ooooAlbert looked at Jeremy Ash who said sharply: “Go find a store up in town, A. Or a phone booth. Call the police. Ask people.”

ooooAlbert had never called the police. In fact, they seemed to spend a great deal of time coming to him. Nevertheless it was apparent, even to him in his state, that Jeremy wasn’t able to get through the sand in his wheelchair without Wendell’s help. It was also evident that Wendell, still performing his inexplicable ritual at a distance, was not going to be performing that function anytime soon. Albert went to get help and, as he did, a voice whispered in his mind: “Albert’s going to get help.” It was an unnatural voice, its words tinged with disbelief and futility. ooooNevertheless, once he had made his way to the nearest store—which sold ice cream and post cards and wood carvings of angry-looking beings—and delivered his message, which was: “There’s a dead girl on the beach,” events seem to unfold of their own accord, as if they were a cue in a play for which the rest of the actors had been waiting. Within minutes he was trailing a little army of people—policemen, medical people, even a fireman, as well as the proprietor of the ice cream shop—to the beach where they relieved Angela of whatever it was she’d been doing.

ooooShe locked eyes with Albert as he made his way to the edge of the activity. “She’s not dead, Albert.” Sweat was dripping from her forehead into her eyes, and she blinked it rapidly away as she attempted to draw him into focus. “I think they may be able to save her.”

oooo“By blowing into her like that?” Albert nodded at the energetic young man who was now doing what Angela had been doing, except that—every five or six times through the procedure—he tilted the girl on her side and alternately pressed her stomach and her chest. None of this had been done gently. Even now bruises were forming on the girl’s flesh.

oooo“That’s a good sign,” said Angela, in response to Albert’s observation. “If she were dead, she wouldn’t be bruising.”

ooooThe part of Albert that had taken refuge in the storm shelter opened the door and peeped out to see if the coast was clear. Its first thought was: “You can save people by pinching their nose and blowing into them?” Why hadn’t anyone told him this when Melissa Bjork lay dying in his arms? Why hadn’t all the dead people who littered his memory been blown back to life? Why hadn’t someone told him to blow into his mother’s mouth as she lay there in her coffin? Maybe she’d have lived long enough to love him. All at once the young man—an ambulance driver, it turned out—started, releasing his mouth from that of the girl and jumping back as if he’d received a shock. The girl’s response was, to Albert, no less alarming. She choked and coughed, and choked and coughed, and suddenly a little geyser of water erupted from her mouth. Her eyes flew open, and she began convulsing. Albert waited for the hairball.

ooooThe next morning there was an article in The New Zealand Herald, which Mr. Sweetman served with breakfast. “To think what might have happened if I hadn’t had Wendell take you there! The poor thing.”

ooooAlbert wasn’t sure to which poor thing the landlord was referring, the girl or Wendell, so he just made an agreeing sound which Mr. Sweetman would have heard if he’d stop talking, which he hadn’t.

oooo“I feel like a positive hero! I mean, of course, it wasn’t me who . . . who found her. But, if I hadn’t had Wendell take you there, well, she’d be dead instead of in the hospital.”

oooo“Only almost dead,” said Jeremy Ash, de-boning a kipper.

ooooAngela tapped the newspaper with her forefinger. “We have to think positively. She’s alive. That’s a start. And we should be thankful.”

oooo“‘In God’s hands now,’” said Jeremy Ash. “That’s what Mrs. Gibson would say.”

ooooThe landlord directed an inquisitive glance at the boy. “Mrs. Gibson?”

oooo“Back home,” said Jeremy Ash. “She’s a . . . “

oooo“His housekeeper,” Angela interrupted, nodding at Albert, who, as usual, wasn’t listening. Sweetman seemed satisfied with the answer.

oooo“How on earth do you suppose she came to be there? That girl? On the beach like that?” Nobody advanced a notion. Not even Jeremy Ash.

oooo“How old would you say she was?” said the landlord, stretching his neck toward Angela.

oooo“Eighteen to twenty-five, I’d guess. Hard to tell, really. Oriental women seem ageless, somehow.”

oooo“Eighteen to twenty-five. Tch, tch. So very sad.” He retracted his neck and leaned back in his chair, with a dollop of oatmeal on his chin. “How very, very sad. And no idea how she got there?” The question was rhetorical. “No signs of violence or . . . or anything of that sort, according to the newspaper. Is that true, do you think?” Albert thought of the bruises, but they were the result of the very efforts that brought her back to life, so it probably wouldn’t be helpful to say anything. Instead, it was Angela who spoke.

oooo“Not that I could tell. But I wasn’t looking for anything like that, so I couldn’t say for sure.”

oooo“Well dressed, it said,” said Sweetman.

ooooThat had been one of the first things Angela had noticed. “Very.” oooo“Odd, that.”

oooo“Why?”

oooo“Well, she can’t have been in the water all that long, seeing’s it was possible to bring her ’round,” Sweetman observed.

oooo“So?”

oooo“Well, that was a little after mid-day?”

oooo“Yes.”

oooo“Most folks along the coast don’t go for dressing up much this time of year. And girls her age? Well, less the better as far as they’re concerned, if you take my meaning.

ooooThe Whangarei area’s thought to be the warmest place in the country. Odd she’d be dressed up like that.”

ooooThe notion hung in the air for a minute, and everyone turned it over in their minds. It was Albert, who hadn’t seemed to be listening, who spoke first. “She was at a party.”

oooo“A party?” said all three of his hearers in such tight unison it was hard to believe they hadn’t rehearsed it.

ooooAlbert shrugged. “Something people get dressed up for in the middle of the day.” Albert himself often got dressed up, but only for concerts, and they were always in the evening. He took that as conclusive proof that the girl hadn’t been dressed for a concert. Of course, he’d gotten dressed up for his mother’s funeral—rather Abigail Grace had gotten him dressed up— in the suit he brought with him to New Zealand, as a matter of fact. Mightn’t the girl have been to a funeral? He studied his memory of her, which was still so vivid he could pick it up and wring salt water from it. Everyone at his mother’s funeral had been dressed, more or less, in black. The girl had been dressed in a . . . well, something not black. Not even a little bit. Not a funeral, then.

oooo“Like a birthday party?” said Jeremy Ash, to which Angela chimed, “or a wedding?”

oooo“Or a cricket match!” said Sweetman.

ooooThat possibility wouldn’t have occurred to Albert in a long sequence of lifetimes.

oooo“Or an art exhibition,” said Angela. “Or a lunch date, or . . . “ ooooThat’s when Albert left the table.

oooo“May I play your piano?” Of all the questions, requests, and intrusions to which Retired Colonel MacAulay Rivens, a.k.a. “Mac,” was conditioned to respond when opening the door, this was not one of them. His tongue did the heavy lifting while his brain tried to figure out what to do.

oooo“I beg your pardon?” it said. And while he was surveying the person to whom his tongue was speaking, he noticed something familiar about the face. Then he remembered. It was the face in the photo in a little silver frame on his wife’s piano.

oooo“I’m Albert . . .”

oooo“You’re him,” the Colonel interrupted. “The man on the piano!” He jerked his thumb at something either over his shoulder or behind him.

oooo“I am?”

oooo“No doubt about it! Come in, come in! Can’t have you loitering about, cloggin’ up the door way.” He drew Albert inside by the hand he’d been shaking and, closing the door behind them, ushered him toward a room with large windows at the end of the hall. “It’s in here.” And so it was, if the “it” he was referring to was a baby grand. “Here, see!” said the Colonel, indicating not the piano, but Albert’s photo in a silver frame. He picked it up—revealing a little oblong of mahogany in the light coating of dust covering the rest of the piano’s surface—and held it out for his visitor to marvel at. Albert glanced at the picture; it was familiar. “May I play?”

ooooThe Colonel, not so non-plussed that he couldn’t allow for the eccentricities of those forming the creative layer of humanity—his wife, Drucie, had been one such. oooo“Please do. She’d be thrilled, my Drucie, to think—well, I don’t know what she’d think.” He opened the lid and propped it up as Albert pulled the bench from under the piano, “You turnin’ up out of the blue like that. I mean, I’d heard you were in the . . . at Sweetman’s, of course. Word gets around, don’t you know. Still, what are the odds? Eh? Damned slim, I’d say.”

ooooAlbert played a chord. Much to his relief, and contrary to his expectations, the instrument was in tune.

oooo“Pretty tone, that,” said the Colonel. “Potty about you, was Drucilla. Absolutely potty. Greatest thing since Marmite in her eyes. That’s what you were. Saw you in concert both times you were here.”

oooo“I’m sorry she died,” said Albert.

oooo“Died? Yes, well. Yes . . . poor old girl. Miss her like blazes, between you and me. Not quite up to . . . well, life without the old thing, don’t you know. How did you know . . . ?”

ooooAlbert explained.

oooo“Ah, old Sweetman. Of course.” He sat beside Albert on the bench, which Albert hadn’t expected. He realized that, in future, he would have to reframe his initial request: “May I play your piano and you go away.”

oooo“Lost his wife, too, did old Sweet. Two years ago.” The Colonel lowered his eyes to the keys, which he brushed with the tips of his fingers. “Hero to me, of sorts. I mean, if he can make it—and thrive, if appearances are anything to go by— well, so can I. Eh?”

ooooOn the last monosyllable he looked at Albert who, coincidentally, was looking at him, trying to channel Angela: “Look like you care,” he challenged himself, and put a great deal of effort into adjusting his face to what he hoped would be interpreted as a caring expression. Actual caring, he hoped, might follow listening. How long after looking like he was listening actual listening would come, time would tell. The Colonel’s eyes suddenly welled with tears, and he collapsed upon Albert’s shoulder and sobbed. A fullthroated sob. Albert was stunned. His hands were still resting on the keys, and he was staring straight ahead—at the photo of himself, at whom he thought: “Well, what do you do now?”

ooooWhat he did was remove the fingers of his left hand from the keys and, placing his arm around the Colonel’s back, patted him on the shoulder. This, it turned out, was what you do when you want a sobbing Colonel to burst into tears outright, which is what happened. Once the dam had burst, there was no holding it back until the reservoir had run dry. Meantime, Albert felt hot tears on his shoulder, and the Colonel’s body quaking against his own, and something strange happened. Albert began shaking, too. And he was shaking because he was crying. And he was crying because his heart was broken. And his heart was broken because Melissa Bjork was dead. And suddenly he remembered why the Colonel was crying. And he cared. And because he cared, he cried all the more.

ooooAnd when the crying passed, they sat up straight, wiped their eyes and their noses with whatever fabric was at hand, sniffed back the last few straggling tears, stood up and shook hands. “Good of you to come, old man,” the Colonel said. “Anytime you want to . . .” He piano-ed the air with his fingers. In silence, they walked to the door and, moments later, Albert was on the sidewalk, looking left and right for the train that had just run him over. It was then he realized it was a train that, deep down, he’d been expecting for a long time, and he’d been tied to the tracks.

ooooHe bent his steps toward Sweetman’s, and having unwittingly reached it, passed it by, his eyes, crusted with the salt of dried tears, focused upon the sidewalk, a blur of concrete rectangles separated by cracks that, somehow, had the mysterious capacity to break one’s mother’s back. Even though Mother was dead, he was careful to avoid them, imagining how the resulting “crack” would sound in the confines of a coffin six feet underground. Probably muted. When he was next aware of himself, he was sitting on a bench in a park. He had no idea how long he’d been there. It was still light out, so it wasn’t evening yet. He’d been thinking. “Lost in thought.” He’d heard that before; now it made sense. Probably a lot of things made sense once you understood them. He’d been thinking about Melissa Bjork. He’d been thinking about Colonel Rivens. About his mother. About the girl on the beach. About Tewksbury—but that was another story.

ooooHe’d thought about himself—something he’d spent the better part of forty years not doing—and the endless, bottomless, ever-flowing river of music that flowed through his brain, like water through plumbing. If he were to understand himself, he’d have to understand where that music came from. People seemed to think it came from him. But he knew it didn’t. It came from somewhere else. Like water. Where did water come from? Not the faucet; that was just the delivery mechanism. That’s what he was. A delivery mechanism. There is a river of music flowing through the universe, he decided, and—for what reason, God only knew—he could tap into it at any time. In fact, it was there all the time. A gift. All he had to do was surrender to it. Fall into it. Swim in it. Let it flow from his fingers onto the keyboard, onto the page. Sometimes it was hard to keep up. But recently the music had changed. Where once it flowed freely without restraint of any kind, lately it was forced through the filter of his experiences of the last four years. Unpleasant experiences. So the river was now, however slightly, tinged with essence of Albert. It was trying to tell his story, but it knew him no better than he knew it. He and his gift stared at one another across a chasm of misunderstanding and shrugged. A mathematical equation formed in his mind: Albert – Music = ?

ooooWhat would be left of him if music were taken away? Just a hole that only Melissa Bjork could fill.

oooo“They been lookin’ for you.” Albert knew the speaker before he looked up and saw Wendell approaching laboriously up a small incline. His was a distinctive voice, and his accent unmistakable. He plopped himself down beside Albert and stared at his fingers for a while.The words implied he, Albert, had been lost. Perhaps he had, without knowing it, and the time had arrived to begin the journey to being found, wherever that might be. “You found me.”

ooooWendell nodded, but didn’t say anything. His breathing was labored and he seemed in need of a rest. At last he spoke. “That girl we found. . .”

ooooThere was no intonation in the statement from which Albert could infer whether it was a question, a statement, or a preamble to an observation. He didn’t know what to say, so he said: “Yes.”

oooo“She woke up. Just for a minute. Said somethin’, then went back to sleep. Coma.” He turned to Albert and explained. “Deep, deep, sleep.”

ooooThis, Albert felt, was the place to begin his journey: He should, on purpose, think about what Wendell had said; then think about what to say about it; then say it. Fortunately, Wendell was perfectly willing to let him take his time.

ooooWhat would Jeremy Ash say? Or Angela? He could almost hear their voices: “What did she say?” So that’s what he said. “What did she say?”

oooo“Venice,” he said. “That’s what they think.”

oooo“Venice,” Albert repeated. “That’s in Italy.”

ooooWendell thought that was probably right. He nodded.

oooo“Or Venice Beach. That’s in California.” A question came to mind all by itself. “Why did she say that?”

ooooIt was Wendell’s turn to shrug. “Maybe she didn’t. That’s what they thought she said.” He picked at his fingernails. “Could have been something else with a ‘v’. Some Chinese word. She looks Chinese. Or Japanese. Or Korean. I can’t tell the difference.” Something with a “v.” There were probably a lot of words that began with “v.” Vivaldi. That had two “v”s. So did vivacity. Vivisection. Lots of “v”s.

oooo“That’s all she said?”

oooo“Mm.”

ooooFor the next fifteen minutes or so, Albert and Wendell sat side-by-side, thinking about whatever came to mind. They might have sat there forever had Wendell not spoken. “Want to go back home?” Albert got up and, in tandem, followed Wendell back to the top of the little mound of sidewalk at the bottom of which was Sweetman’s. He was mildly surprised, but not shocked, to find a cluster of newspaper and television people waiting outside. “What’s all this?” Wendell wondered.

oooo“Reporters,” said Albert. Were they here for him? Why? He didn’t have any concerts planned. Why else would they want to talk to him? Perhaps they were talking to Jeremy Ash or Angela . . . or Mr. Sweetman. They’d all be interesting.“Is there a back door?”

oooo“Sure, bro,” said Wendell, and directed Albert to the rear entry. From there, he went upstairs to his room, and Wendell went to tell the proprietor he’d “found the piano player.”

ooooA few minutes later, there was tap on his door. “Albert?” Angela opened the door as she spoke, and poked her head around the corner to find him sitting in a chair by the window, overlooking the little garden at the back of the house. “Are you okay?”

ooooAlbert was never quite sure how to answer that question, because he didn’t know the answer. Okay compared to what? But he gave the answer that generally resulted in the least follow-up. “Yes.”

ooooShe came toward him, preceded only a moment by her smell, which Albert had come to enjoy. It never occurred to him that the fragrance might be perfume, or soap, or furniture polish or anything else. He’d just assumed it was her smell, and it was a pleasant one. Some people were blond, some brunette. Some smelled nice, some didn’t. Way of the world. Jeremy Ash smelled of medicine and bandages. And laughter. Mrs. Gibson smelled like whatever she’d been cooking. Did he smell like music? What did music smell like?

ooooHe hoped, at any rate, it was a pleasant smell, because it’s what Angela would smell as she sat on the arm of his chair. She ran her hand through his hair, casually, as if that’s what she always did—which it wasn’t—and that it was perfectly natural. What happened then didn’t bear thinking about, so he tried to think about what she was saying, rather than what she was doing—which, from his perspective, had a lot in common with open heart surgery.

oooo“Went for a little walkabout, did we?”

ooooDespite his best efforts, his body was listening much more closely to her fingers than her words. He was about to ask her to speak up. But she continued. “You had me worried.”

oooo“What about?”

oooo“About you.”

oooo“Why?”

oooo“I didn’t know where you’d gone.” Albert considered this and was about to say, “Neither did I,” but realized that wouldn’t be entirely true, would it? He’d gone to the park, whether he meant to or not, and just stopped walking when he got there. “That girl woke up and said something,” he said. Angela responded fluidly to the deflection.

oooo“Yes. ‘Venice’, they think. Something like that. Wendell told you?” She kept slowly dragging her fingers through his hair. She’d never done that before. She’d never leaned against him like she was leaning now. She wasn’t heavy, or if she was, that’s not what he noticed. What he did notice was that she was very warm and soft in places.

oooo“Yes.” He leaned away a little.

oooo“Oh, sorry,” she said, sitting up straight and taking her fingers from his hair at the same time. “I didn’t mean to make you uncomfortable.” If that was her intention, he thought, she’d gone about it the wrong way. As soon as she was no longer connected to him, he felt like he’d fallen through a whirlwind into a void. He preferred the whirlwind.

ooooFor her part, how could she sit there and not run her fingers through his hair? That would be like not petting a particularly lost and sorrowful puppy. Inhuman. She stood up and walked to the open window from which she looked down upon the garden. “Beautiful, isn’t it?” She was now standing between him and the window, and the light from the window was shining through her skirt, or dress, or kimono, or nightgown or whatever it was, and, well, yes, it was beautiful. He wondered what Melissa Bjork would look like, standing there with the light shining through her—thing.

oooo“What do those reporters want?” he said. She turned toward him, and he struggled to keep his eyes on her eyes rather than what they wanted to look at.

oooo“You, of course. Good thinking, slipping in the back door like that. I don’t think they gave you credit for that kind of deviousness.”

oooo“It was Wendell’s idea.”

oooo“Ah.”

oooo“Why?”

oooo“Why what?”

oooo“Why do they want to talk to me?”

ooooShe giggled, turned to him and, placing a palm on each arm of his chair, leaned over him. “Think, Albert. Why would they want to talk to one of the most famous musicians in the world—one who’s been involved in a chain of mysteries lately—and who, incidentally, just happened to discover the body of an unknown girl on a local beach?”

oooo“That wasn’t me. It was you, and Jeremy Ash.” Much to his relief, she stood up and began pacing back and forth behind his chair.

oooo“Nonentities, as far as the press is concerned. Appendages. You are the story. Like it or not.”

ooooHe didn’t feel like a story. He felt, once again, like the “X” that marked the spot where the accident happened, and it was not a good feeling.

oooo“Jeremy’s keeping them out in the cold, of course,” she continued. “‘Reporters Stampede Legless Boy!’ Not a good headline. He ‘plays upon them as upon a stringed instrument’, as Jeeves says. They’ll give up and go before much longer. It’s starting to rain.” She ruffled his hair. “Dinner’s ready. Come on down.” She turned toward the door. “What do you think she meant?”

oooo“Who?”

oooo“The girl on the beach,” Albert said. “Why did she say ‘Venice’. What did that mean?” She came back and settled herself on the floor at his feet. This time, without even thinking about it, it was he who ran his fingers through her hair. When she spoke, he realized what he was doing and immediately pulled his hand back.

ooooShe looked up at him, her eyes thick with honey or novacaine or something. “You don’t have to stop.” She took his hand and put it on her head, where it sat in silence for several seconds, and he looked at it as if it was a foreign object, and wondered what it would do. When it did nothing of its own accord, he took it back. “Anyway,” she said, folding her legs under herself and standing up without using her hands, at which Albert marveled, “you might want to tidy up a bit, then come on down to join us.”

ooooA moment later, she was gone.

ooooWhat had just happened? he wondered, but quickly realized that finding answers to that question would probably turn him inside out, and he’d been turned inside out enough lately. What had she meant by “tidy up?” Should he bathe? Shower? Shave? Comb his hair? Clean his fingernails? Find a tuxedo? All the above? It was a relative term, entirely unrelated to him. He ran his fingers though his hair, bent over to look in the mirror and, seeing there pretty much the same person he’d always seen—perfectly recognizable—went down to dinner.

ooooOnce the conversational niceties were over and everyone was on the same page regarding his whereabouts since lunch, Jeremy Ash brought him abreast of the latest news about the Girl on the Beach. “The police don’t have a clue who she is,” he began enthusiastically. “They had her picture on the news . . . and yours, of course.”

oooo“On the telly, all afternoon,” chirped Mr. Sweetman.

oooo“. . . and the morning paper,” Jeremy Ash resumed.

oooo“They’re offering a reward,” said Wendell from the far end of the table. “$5,000.”

oooo“That’s about $2,500 in real money,” said Jeremy Ash.

ooooMr. Sweetman inhaled to fuel his objection but, being a gentleman, was silenced when Angela joined the conversation. “Not a word from anyone. No relatives. No friends, schoolmates. No one—and the pictures have run all over the country.”

ooooAlbert was eating his soup and trying to quiet the music Angela’s visit to his room had conjured in his brain. It was with this cacophony that the ambient conversation had to contend for his attention. “She’s not from New Zealand,” he said, almost without thinking. ooooSpeculation—which is what the conversation had devolved to—came to a stop.

oooo“What do you mean, A?” said Jeremy Ash.

ooooAlbert, still staring into his soup—still trying not to think in 9/7 time, which is what that music was—slowly realized a comment had been directed at him. He looked up, first at Angela, then at Jeremy. “What?”

oooo“You said she’s not from New Zealand.”

oooo“Who’s not?”

oooo“The Girl on the Beach, A,” said the boy in frustration. “We’re talking about the Girl on the Beach. You said she’s not from New Zealand.”

oooo“Did I?”

ooooEveryone nodded.

oooo“Well, she’s not.”

oooo“But why do you think that?”

ooooAlbert tilted his head slowly from side to side, sifting the question through his cognitive apparatus. “It’s not what I think. It’s what is.”

oooo“He’s making me crazy,” said Jeremy Ash, pushing his wheelchair back from the table.

oooo“What do you mean, Albert?” Angela prodded gently. His thoughts were not normal thoughts, she knew—and she’d been frustrated to the point of manslaughter many times over the last year—but she was determined, knowing that Albert would never change, to adapt herself to his way of thinking. If only she could figure out what that was. “What’s the difference between think and is?”

ooooThis was a reasonable question, Albert thought. He decided to think of a metaphor, which took a while. “I don’t have to think if a note is sharp or flat,” he said at last. “It is, whether I think it or not.”

oooo“And this applies to the Girl on the Beach how?” Angela asked patiently.

oooo“New Zealand’s a small country. If everyone has seen a picture of her, or heard about her on the radio, and nobody’s reported her—or someone like her—missing, then she must be a stranger. She’s from somewhere else.”

oooo“Of course!” said Mr. Sweetman, nearly jumping from the table. “A tourist!” A chorus was raised in agreement. It made sense. Nobody had reported her missing because nobody knew her. “Plain as day,” Sweetman continued. “Went for a wade, tripped and fell somehow, bumped her head and . . .” He projected his head toward the company. “Plain as day. Accident!”

ooooA tourist? For some reason Albert’s head wasn’t nodding with the rest. Something was odd, and he tried to remember what it was. There was a guide in his brain, he’d come to realize of late—always just out of sight, just around the next bend—that would call to him at times like this. It called to him now. “This way, Albert. This way!” He steadied his thoughts with a sip of soup and concentrated on following. It took him to his memory of the beach. Not the Girl. The beach. He had noticed something as he’d stumbled toward the surf. What was it? ‘Look around, Albert. Look around.’ He surveyed the memory. “No footprints,” he said aloud.

oooo“No footprints where?” said Jeremy Ash.

ooooAlbert sat up, sorted out his thoughts, and spoke them. “There were no footprints on the beach,” he said. “Just ours. So the girl hadn’t been wading, at least not on that beach. There were no other beaches around. Just cliffs. But she didn’t jump or fall from a cliff.” oooo“Clearly not,” Angela agreed. “She’d have been all beat up—and probably not alive.”

oooo“So,” Albert concluded, “she came from the ocean.” Even the voice in his head had been silenced by that deduction. Albert resumed eating his soup—some kind of seafood or chicken or vegetables, probably. There were potatoes in it, he was sure of that. Of course, this being New Zealand, they might not be. It was good, though he’d have preferred it hotter.

ooooHis companions at the table tossed brief, interrogatory glances at one another; then fell to studying the auguries in their bowls for answers to the questions Albert’s declaration called forth. Jeremy Ash, not uncustomarily, was first to speak. “She’s not a mermaid, A. What do you mean she came from the sea?”

ooooAlbert was bent over his bowl. “If she didn’t come from the land, it’s the only place she could have come from.”

oooo“Could’ve come from the sky,” said Jeremy Ash.

ooooAlbert hadn’t thought of that. “Or the sky.”

oooo“I was just kiddin’, A. She didn’t fall from the sky.”

ooooThat was good. If she’d fallen from the sky, that would make things much more difficult. “No. Not from the sky,” said Albert, a little relieved. “From the ocean.” oooo“But she didn’t start out in the ocean,” Angela said. “She had to have started somewhere. Where?”

oooo“What’s in the ocean?” Albert asked, as if proposing a riddle to which he already knew the answer. Which he didn’t.

oooo“Islands,” said Wendell.

oooo“Ships,” said Jeremy Ash.

oooo“Islands and ships,” Albert repeated. “Then that’s where she came from. An island or a ship.”

oooo“I wonder if that’s what the police reckon,” said Sweetman. As if on cue, the front doorbell rang and, seconds later, the maid preceded the visitor into the room. “P’lice to see you, Mr. Sweetman.”

oooo“Senior Sergeant Hawkes,” said a tall, uniformed man as he entered the room, and stationed himself at the head of the table directly behind Sweetman, who had to turn in his chair to see him; an acrobatic feat for someone of his age, and not without discomfort. “I’m sorry to interrupt your meal,” he said, without seeming sorry at all, “and apologize for not coming to see you sooner about this business of the Girl on the Beach. Suicide attempt, of course. Very sad. But now we’ve had a chance to clear a few things up, I’d like my sergeant here . . .” It was then he realized that his sergeant wasn’t here but, judging from the giggles in the hallway, entertaining the maid. “Jeffreys! In here at once!” At once, Jeffreys was there. “As I said, Jeffreys here will take your statements so we can enter them into the record. Just a formality.”

ooooHe turned partway toward the door, putting his cap back on his head. “Once again, apologies for the intrusion. Enjoy the remainder of your visit to God’s country.” ooooAlbert had finished his soup. He was looking at Hawkes. “She didn’t try to kill herself,” he said.

ooooThe policeman was arrested, his hand on the doorknob. “I beg your pardon?” He scanned the faces at the table. “Did someone say something?”

ooooJeremy Ash spoke up. “She didn’t attempt suicide.”

oooo“’Course she did, young man. Plain as day. Now, if you’ll all just give Jeffreys your statements, you can get on about your business. Good evening.”

oooo“She came from the ocean,” Albert said. Once again, Hawkes was prevented from leaving. Being of British stock, he was not accustomed to anything that might be seen as a challenge to his authority. “Who spoke?” he said, turning and removing his hat.

oooo“I did,” said Albert.

oooo“And you are?”

ooooJeremy Ash supplied the basic information.

oooo“Professor, is it?” said Hawkes. “Professor of what?”

ooooAgain, it was not Albert, but Jeremy Ash who spoke. “Music.” oooo“He’s a concert pianist,” said Angela, attempting to clarify. oooo“Very famous,” Sweetman added. “Very famous.”

oooo“Well, Mr. Famous Piano Player,” said Hawkes for whom, apparently, piano players did not figure high in his estimation. “You said?”

oooo“She came from the ocean,” Albert repeated.

oooo“We all did, they say,” said Hawkes, laughing and, with a swivel of the head toward his sergeant, enlisting that subordinate to do the same. “It’s called evolution.” No one else was laughing. “Go on,” said the senior sergeant. “What do you mean she came from the ocean?” ooooAlbert explained.

oooo“A ship!” said Hawkes, once again with a caustic laugh. “You mean to say she jumped from some passing ocean liner and swam all the way to shore?”

ooooIs that what he meant? “Maybe.”

oooo“Absurd,” Hawkes huffed, then echoed himself, “absurd.” He turned once again to his sergeant, in expectation of affirmation, which was immediately forthcoming.

oooo“If she’d fallen from a cruise ship, they’d’ve reported her missing.”

ooooAlbert took that in. It made sense. “Then it wasn’t a cruise ship.”

oooo“Good! I’m glad we’re agreed. Now, if you’ll all just . . .”

oooo“It was some other kind of ship.”

oooo“Such as?” Hawkes snapped. “A spaceship?”

ooooThey’d already ruled out a fall from the sky. “No. Some other kind of ship.”

oooo“Such as?”

ooooAlbert shrugged.

ooooJeremy Ash answered. “A sailboat? A yacht? A fishing boat? A ferry? A canoe?” Albert loved Jeremy Ash. “One of those,” he said.

oooo“Once again, absurd,” said Hawkes. “Had she fallen or jumped from any of those, they’d’ve let us know so we could launch rescue operations. Now, if that’s all . . .”

ooooIt wasn’t.

oooo“What if she didn’t fall or jump?” The thought had occurred to Albert’s brain and tongue simultaneously. “What if she was pushed, or thrown in?”

ooooAngela took up the thread. “If someone was trying to kill her, then of course no one would have reported her missing!”

oooo“It fits, Sergeant,” said Sweetman.

oooo“Senior sergeant,” Hawkes corrected. Not only had his epaulets been ruffled, but his hypothesis as well. And now he was questioning it himself. So he said the only thing that came to mind, but without conviction. “Absurd.”

oooo“Why?” said Angela.

oooo“Why what, young lady?”

oooo“Why is it absurd to consider a possibility that fits all the facts?”

ooooHawkes, who had begun to sweat around the eyes, manufactured a condescending smile as he put his hat on. “Just you leave the policing to the professionals, missy. You’ll find that every contingency is taken into account. Suicide, no doubt about it. Sergeant? Take their statements.” He bowed curtly and left in haste.

ooooSergeant Jeffreys took their statements and, as he was leaving, addressed the room—Albert in particular, though he was looking at Angela. “If asked, I’ll deny I ever said this, but your theory makes more sense than anything we’ve come up with at HQ. I’m just a humble sergeant, but I’ll see if I can’t give things a nudge.” He closed his notebook with an efficient snap, winked, and went away. There was more giggling in the hallway as the maid showed him to the door. ooooJeremy Ash was ebullient. “Here we go again,” he said.

ooooAlbert didn’t want to go again.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I hope you’re sufficiently intrigued by these sample chapters – and by Albert – to download the rest of Improvisato to your Kindle, Nook, iPad, iPhone or other reading device. To do so, simply

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I hope you’re sufficiently intrigued by these sample chapters – and by Albert – to download the rest of Improvisato to your Kindle, Nook, iPad, iPhone or other reading device. To do so, simply

or click the book cover at the top of this page which will take you to Amazon where you can place your order safely and securely. And if you enjoy Improvisato be sure to download the presequels, https://www.amazon.com/Requiem-Ashes-David-Crossman-ebook/dp/B07W4NNJWD/ref=sr_1_fkmr0_1?keywords=david+crossman+improvisato&qid=1573099274&sr=8-1-fkmr0Dead in D Minor. Meanwhile, PLEASE Facebook, Twitter, or e-mail everyone you know and send them to http://www.davidcrossman.com!